In the 1970s, a psychiatrist named Jerome Motto demonstrated that non-demanding caring letters could prevent suicide among high-risk individuals.[1,2] Motto suggested that a suicidal person’s sense of isolation would be reduced, and feelings of connectedness enhanced, by long-term contact with someone concerned about that person’s well-being. To be effective, this contact should be initiated by the concerned individual and place no demands on the recipient. Today, Motto’s caring letters intervention remains one of the only interventions to show a reduction in death by suicide in a randomized controlled trial.[3]

In the 1970s, a psychiatrist named Jerome Motto demonstrated that non-demanding caring letters could prevent suicide among high-risk individuals.[1,2] Motto suggested that a suicidal person’s sense of isolation would be reduced, and feelings of connectedness enhanced, by long-term contact with someone concerned about that person’s well-being. To be effective, this contact should be initiated by the concerned individual and place no demands on the recipient. Today, Motto’s caring letters intervention remains one of the only interventions to show a reduction in death by suicide in a randomized controlled trial.[3]

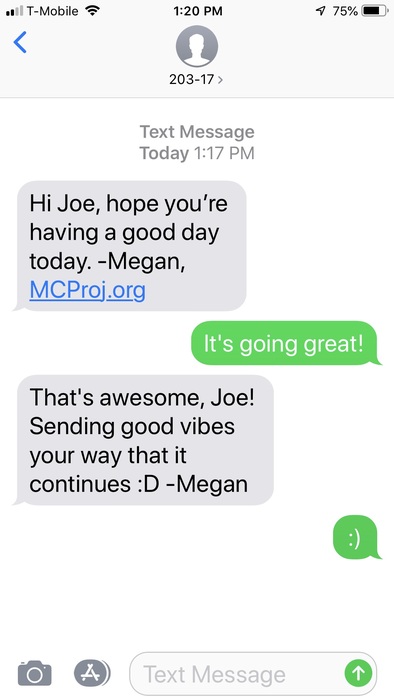

Based on Motto’s intervention, but using 21st-century technology, Comtois and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial of a Caring Contacts via text message intervention with active duty Soldiers and Marines at risk for suicide.[4] 658 participants were randomly assigned to receive 11 Caring Contacts over 12 months in addition to standard care or standard care alone. Caring Contacts were authored by a study clinician who had met with and gotten to know each participant during a baseline assessment. Caring Contacts in this study were brief and focused solely on expressing care, interest, and support, e.g., “Hey Joe- hope things are going well and you’re having a good week.” When participants replied, study clinicians responded according to a study protocol that was ultimately revised to allow for natural, caring interaction, e.g., responding to “I’m good this week” with “I’m so glad to hear it!”

Contrary to hypotheses, augmenting standard care with Caring Contacts did not reduce current suicidal ideation at 12 months or hospital-based care to prevent suicide. However, Caring Contacts led to a 44% decrease in the odds of reporting any suicidal ideation during the follow-up period and a 48% decrease in the odds of reporting one or more suicide attempts since baseline compared to standard-care. This inexpensive and scalable intervention offers promise for preventing suicide attempts and ideation in military personnel.

Read the publications associated with this study.

References

Additional Resources